|

|

| |

By Nick Upton 24/03/06

Research

Techniques Assignment 1

BSc (Hons) Wildlife and Countryside Conservation,

Year 2

Note:

This essay is not intended to be a thourough scientific

review of the known ecology of White-eyed

River-Martin nor is intended to by an attack on

the orignal article by Joe Tobias who I hope will

be flattered to know that out of millions of articles

I could have chosen to review it was his that

interested me enough to do so. The remit I was

given for this assignment was to choose an article

from a peer-reviewed publication and write a balanced

critique of it, with the highest grades given

to those who are able to show a high level of

critical thinking and originality. I have included

my work here as I feel that some of the points

I make will be of interest and may stimulate some

thought upon the subject which in turn may contribute

to rediscovering this species if it still exists;

something that was also the intention of the original

article which is reproduced here in the appendices

with kind permission of the Oriental

Bird Club (OBC) and referred to throughout

the essay by paragraph number.

Please

support the OBC's conservation work by visiting

their website and becoming a member.

Contents

1.

Introduction

2.

Literary Style

3.

Factual Accuracy and Analysis

4.

Conclusion

5.

References

6.

Appendices |

|

|

| |

Introduction

Figure

1: White-eyed

River-martin (McClure, No date). |

|

Even a cursory glance at one of the few photos

in existence of the White-eyed River-martin

(See figure 1) immediately conveys a feeling

that it is a special creature, indeed, it

has something about it that makes one wonder

if it is in fact a real species and not a

clever hoax. Add to this its mysterious discovery

and disappearance, and the unusually low number

of these birds that have ever been encountered,

and the result is a bird of almost mythical

proportions. This article attempts to clarify

some of the facts that have become clouded

since its discovery in 1968 (Thonglongya),

to summarize the speculation surrounding its

ecology and taxonomy, to rekindle hope that

it may be rediscovered by proposing areas

where it may persist and ultimately to introduce

a new generation of ornithologists to a little-known

and neglected species. To achieve this, the

author employs a blend of historical narrative,

extrapolation and speculation from scientific

fact with an informal style of writing.

m |

|

|

|

| |

Literary

Style

From the beginning of the article the author attempts,

rather successfully, to create an almost fairy-tale

like atmosphere, giving the reader an early sense

of how mysterious this species is and by using vocabulary

such as “spectacular”, “enigma”,

“mythical” and “cryptic”

from start to finish, the reader is constantly reminded

of this theme. This element of mystery is created

by placing the reader at the scene of discovery,

making one feel part of the story from the first

paragraph; setting the scene for suggesting that

the reader has a part to play in the rediscovery

of the species towards the latter stages of the

discussion. By employing this style, the author

has created a connection between the reader and

the River-martin that not only results in reading

the article to completion, but hopefully continues

beyond by stimulating the reader to interpret the

facts in their own way and to make further research

into the subject. A discussive style of writing

also helps to keep the reader at the centre of the

article and by asking questions before answering

them (Paragraph 7), it almost feels like one is

having a conversation rather than reading an article.

The system of referencing by numbers adds to this

high level of readability, maintaining the flow

of the argument without confusing the eye with large

amounts of names in brackets or italics, although

this is contrary to the system used by many authors.

These points all draw the reader further into

the article once it has been commenced, but a

certain aspect of the layout does not add to its

attraction; there are no sub-headings to break

the script into more digestible chunks for the

reader with lower powers of concentration. It

might be useful for the author to use headings

such as “Discovery”, Ecology”

or “Where to look” to give the reader

an at-a-glance summary of the topic of each section.

This is a minor point, but as it seems that widening

the awareness of the White-eyed River-martin is

an aim of the article it would seem sensible to

employ tactics designed to attract as large an

audience as possible.

Although the style of writing is largely excellent

in terms of the atmosphere it creates and in its

clarity, the second paragraph is uncharacteristically

unclear in the way it attempts to explain that

knowledge of the precise site of discovery may

not be as reliable as is often stated. This is

cleared up in the third paragraph, but it remains

that the information in paragraph two is rather

clumsily delivered. By using the words “Bung”

and “Nong”, an assumption that the

reader has some knowledge of the Thai language

is made and this is ill-advised, further confusing

the point, and when a poor translation is also

used (fen would be more appropriate (Pers. Obs.;

SE-Education, 2002; Phiromyothee, 2006)) it does

not help the reader paint a clear picture of the

site of discovery.

Paragraph

two apart, the style of the article is interesting,

it is easy to understand and very readable.

Factual

Accuracy and Analysis

Before

examining the factual content of the article,

or any of the explanations it offers, it should

be praised for bringing the story of the River-martin

to a wider audience. If the reader is tempted

to further his research on the subject, it immediately

becomes clear how difficult this is to achieve

with most of the referenced articles being difficult

to obtain due to their age or storage in Thai

libraries. In this respect, this article does

a wonderful job of bringing the entire White-eyed

River-martin story a new level of accessibility

through the traditional media of scientific bulletin

and, for the first time, through the internet.

The

first nine paragraphs of the article outline the

circumstances surrounding the discovery and disappearance

of the species, and these facts are hard to dispute.

Indeed, the author does a good job of questioning

the accuracy of what has been long taken for fact,

highlighting that the original research team never

actually saw the species in the field (Paragraph

3). The author does, however, fall short of specifically

pointing out that this included Kitti Thonglongya,

who originally described the species (Birdlife

International, 2001); this point would have given

weight to the theme of keeping an open mind to

the accuracy of some of the original reporting.

Whilst speculating on the location of roosting

Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica, and consequently

where the River-Martin might be located, the author

does well to highlight the changing ecology of

Beung (Bung) Boraphet due to lotus harvesting

(Paragraph 9), but completely omits to mention

that the fen was totally drained of water in 1959

and 1972 (Jintanugool & Round, 1989) and again

in the early 1990s (Stewart-Cox, 1995), with further

disturbances during this latter period (Round,

1990). These facts have surely effected the stability

of the ecosystem and could prove critical to whether

the site remains suitable for White-eyed River-Martin.

This section of the article also informs the reader

that a reserve ranger was killed by poachers at

Beung Boraphet; very useful in providing an insight

into the problems of conservationists in Asia,

as well as rather macabrely adding to the mystique

of the narrative. |

|

|

| |

Figure

2: African River-Martin (Sinclair,

2004). |

|

The remainder of the article discusses the

possible ecology of this species in order

to speculate upon where rediscover might occur,

and in doing so draws the reader’s attention,

in paragraph 10, to another little-known species,

the African River-Martin Pseudochelidon

eurystomina. As the closest relative

of White-eyed River-martin this is a natural

progression of the discussion, but despite

providing excellent photos of sirintarae

there is no image of eurystomina

for comparison (See figure 2); whilst this

is not a necessity it would be of interest

to the reader. Having invited comparison with

the African species, the author fails, at

this point, to explore this line of thinking

further, instead a summary of what can be

inferred from the few specimens ever studied

is provided. |

|

|

|

| |

These facts are of obvious merit, however, it

would make sense to alert the reader to these

before suggesting a look at African River-Martin

and then to subsequently discuss its affinities

to sirintarae in entirety.

Speculation

based upon African River-Martin’s behaviour

is made without properly discussing the most critical

point when assessing the merits of this theme;

in which genera are the two species to be placed?

Mentioned in only fragmentary form, in paragraph

four and in the penultimate paragraph, is the

fact that some authors consider sirintarae

deserving of its own genus and others consider

it congeneric with eurystomina. To so

briefly deal with this issue, and in broken fashion,

would seem rather a pity, as the two species’

similarity, or difference, is vital when assessing

the possible ecology and behaviour of White-eyed

River-Martin; issues that are critical when speculating

upon where it might be rediscovered due to the

scarcity of factual information. Presumably this

author considers that sirintarae should

be placed in the genus Eurochelidon as

this is the taxonomy used in the article’s

title, but no explanation as to why this view

has been taken is given other than a few anecdotal

observations (Paragraph 4). Perhaps this is because

this view does not really hold up to scrutiny;

on re-analysis of the data taken from the original

samples there is apparently no significant difference

in the bill measurements of the two species (Zusi,

1978), previously the only non anecdotal evidence

for different feeding ecologies and thus different

genera (Turner & Rose, 1994). When it is also

taken into account that the decision to place

sirintarae in its own genus was based

on data from just nine to twelve samples, certainly

not enough to be conclusive, it may explain the

author’s reluctance to discuss this issue.

Whilst the author does well to encourage the reader

to keep an open mind regarding the behaviour and

ecology of White-eyed River-Martin throughout

this section of the article, he might do better,

considering the lack of evidence to the contrary,

to concentrate on using African River-Martin as

a model when considering the habits of the Asian

species.

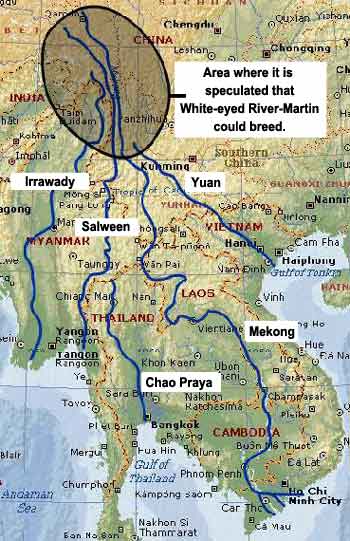

The

article does in fact follow this theme up to a

point, going on to propose regions that would

most likely harbour this elusive species if it

still exists, and this optimistic aspect is vital

for the article to inspire any ornithological

expeditions. Assumptions about sirintarae’s

ecology here are indeed drawn from knowledge of

African River-Martin in that large river systems

(Turner & Rose, 1995; Birdlife International,

2000) are deemed the most likely regions to examine;

with rivers in Thailand, Myanmar, China, Laos

and Cambodia all suggested. The author does well

to name the last of these as since publication

there have been possible, if unconfirmed, sightings

of White-eyed River-Martin there (Silver, 2003;

Judell, 2006). However, this is simply recycling

established views and although the stated aim

is just this; “to compile our knowledge”

(Paragraph 1), the author would be well advised

to provide a new interpretation to improve the

chances of achieving another stated aim; “in

hope that it might lead to a dramatic rediscovery”

(Paragraph 1). Indeed, it is here that the author,

having made comparisons with the African species,

stops short of further extrapolation; it is known

that the African River-Martin breeds inland and

migrates down the Congo river to winter in coastal

regions (Birdlife International, 2000; Birdlife

International 2005), so why not consider that

the Asian species behaves the same? It has often

been suggested that sirintarae might

breed somewhere in China and migrate (Dickinson

& Dekker, 2001), so the author does well to

suggest the Salween, Irrawady and Mekong, but

he would be well advised to consult an atlas to

see that the Yuan in Vietnam would be equally

likely (See figure 3). Indeed, this river, and

the delta of the Mekong, would surely deserve

consideration in respect of the number of scientific

discoveries, and rediscoveries, in Vietnam since

the end of the war. If beasts as large as the

Vu Quang ox (Dung et al., 1995) and Javan

rhinoceros (Newsweek International, 1999) can

go unnoticed then surely there is hope for a bird

as small and as mobile as the White-eyed River-Martin?

m |

|

|

| |

Figure

3: River systems that could harbour

White-eyed River-Martin (Adapted from Microsoft,

2006). |

|

A

short article like this does well to touch

upon, if sometimes too briefly, so many issues,

and it may well be the intention of the author

to simply provide a spark to rekindle a forgotten

debate, and in this he has done well. One

issue, though, does not seem to have been

dealt with at all; the possibility that White-eyed

River-Martin might only have ever occurred

in Thailand as a vagrant, something others

have subsequently proposed (Birdlife International,

2001). It is mentioned that the species was

assumed to be regular in this country because

the locals knew it by the name nok ta phong,

“swollen-eyed bird”, however,

this is a name so simple that it could have

been made up on the spot by even a child,

and carries no implication that it is a long-standing

name. The article does observe, though, that

rediscovery is most likely in another country,

but by refusing to outline the possibility

of vagrancy, denies the reader a vital clue

to rediscovering the species. In this theme,

the article

could have gone on to suggest analysing weather

patterns at the time of discovery in 1968

to see if anything unusual occurred. In fact,

this reluctance to discuss vagrancy is perhaps

similar to omitting a full discussion of taxonomy

in its Siamocentricity, a line of thought

that may have held back rediscovery of the

species and may continue to do so. |

|

|

|

| |

The final paragraph of the article sees the author

back to his best, with a splendidly optimistic

and atmospheric summary of the likelihood that

rediscovery will occur, pointing out the fact

that it escaped ornithologists attention for a

long period before being discovered. The last

sentence, in particular, is well-designed to encourage

the reader to further investigate the species

and possibly claim his “prize”.

Conclusion

This

article does an excellent job in collating the

current knowledge of the species and revealing

avenues of further thought that the reader might

take when considering this species. The style

of writing is interesting, upbeat and atmospheric,

although at times the structure of the discussion

does not seem as logical as it might. The author

does well to draw attention to using the African

River-martin as a comparison, but stops short

of exploring the full range of possibilities this

might lead to, even failing to recognise some

of the basic inferences one might draw from this.

There is also a failure to provide any conclusive

evidence to explain why African and White-eyed

River-Martins should not be considered congeneric;

something that is at the centre of deciding upon

their behavioural similarities or differences

and consequently where the search for sirintarae

might resume.

It

can be said that the author achieves his stated

aim of compiling current knowledge in an informative

and thought-provoking way. By provoking the reader

to question the facts, the author also goes some

way to stimulating the road to rediscovery, but

by not taking the opportunity to follow his train

of thought to its conclusion he fails to make

any ground-breaking speculation of his own to

further this aim. Indeed, since publication a

breakthrough has yet to be made (Butchart et al.,

2005).

References

Birdlife

International (2000). Threatened birds of the

world. Barcelona & Cambridge, UK.

Birdlife

International (2001). White-eyed River-martin

Eurochelidon sirintarae, Red Data

Book; Threatened Birds of Asia. Online at

http://www.rdb.or.id/detailbird.php?id=257

[Accessed 21/02/06].

Birdlife

International (2005). African River-martin; Birdlife

Species Factsheet, Birdlife International

website. Online at http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/index.html?action=SpcHTMDetails.asp&sid=70

[Accessed 22/03/06].

Butchart,

S.H.M., Collar, N.J., Crosby, M.J & Tobias,

J.A. (2005). Asian Enigmas: “Lost”

and poorly-known birds: top targets for birders

in Asia, Birding Asia-Bulletin of the

Oriental Bird Club, No 3, June

2005.

Dung, V.V., Giao, P. M., Chinh, N. N., Tuoc, D.

& MacKinnon, J. (1995). Discovery and conservation

of the Vu Quang ox in Vietnam, Biological Conservation,

Vol 72, No 3, pp 410-410(1).

Jintanugool,

J. & Round, P. D. (1989). Beung Boraphet,

Asean Regional Centre for Biodiversity Conservation

(ARCBC) website. Online at http://www.arcbc.org/wetlands/thailand/tha_beubor.htm

[Accessed 02/03/06].

Judell,

D. (2006). Personal communication.

McClure,

H. E. (No date). Photograph of White-eyed River-martin

reproduced in Tobias, J.A. (2000). Little-known

Oriental bird, White-eyed River-martin Eurochelidon

sirintarae, Oriental Bird Club Bulletin

31; June 2000.

Microsoft

Corporation (2006). Encarta Atlas online.

Online at http://encarta.mas/encnet/features/MapCenter/map.aspx

[Accessed 28/03/06].

Newsweek

International (1999). In Vietnam, a Shot in the

Dark (first photograph of the world’s most

endangered animal, a Javan Rhino in Vietnam).

Newsweek International, July 26, 1999.

Phiromyothee,

S. (2006). Personal communication.

Round,

P. D. (1990). Bird of the month: White-eyed River-martin.

Bangkok Bird Club Bulletin, Vol

7, No1, pp10-11. Cited in Tobias, J.

(2000). Little-known Oriental bird, White-eyed

River-martin Eurochelidon sirintarae,

Oriental Bird Club Bulletin 31;

June 2000.

SE-Education

(2002) SE- ED’s Modern English-Thai

& Thai-English Dictionary (Contemporary

Edition). SE-Education, Bangkok, Thailand.

Silver,

G. (2003) Bangkok Morning/ Prek Tol, Cambodia

Trip Report. Birdchat Website. Online

at http://listserv.ccit.arizona.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0302d&L=birdchat&O=D&P=3796

[Accessed 24/03/06].

Sinclair,

I. (2004). Photograph of African River-martin

reproduced in Trip report from Gabon, Sao Tome

& Principe, and Camaeroon, 14 February –

11 March 2004, Tropical Birding website.

Online at http://www.tropicalbirding.com/tripreports/STP-Cameroon-Feb2004FEW-pix.htm

[Accessed 23/03/06].

Stewart-Cox,

B. (1995). Wild Thailand. Asia Books,

Bangkok, Thailand.

Thonglongya,

K. (1968). A new martin of the genus Pseudochelidon

from Thailand. Thai National Scientific Papers,

Fauna Series no 1. Applied Scientific Research

Corporation of Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand. Cited

in Tobias, J. (2000). Little-known Oriental bird,

White-eyed River-martin Eurochelidon sirintarae,

Oriental Bird Club Bulletin 31;

June 2000.

Turner,

A. & Rose, C. (1994). A Handbook to the

Swallows and Martins of the World, Christopher

Helm, London.

Zusi,

R. L. (1978). Remarks on the generic allocation

of Pseudochelidon sirintarae. Bulletin

of the British Ornithology Club, Vol

98, No 1, pp13-15.

Appendices

Appendix 1:

Little known Oriental Bird: White-eyed River-Martin

Eurochelidon sirintarae by Joe Tobias

Paragraph 1 In January

1968, during the course of ringing activities

at a wetland site in south-central Thailand, fieldworkers

discovered a strange swallow amongst large numbers

of migrant hirundines. It proved to be a new species

and was christened the White-eyed River-Martin

Pseudochelidon sirintarae by Kitti Thonglongya

who dedicated this spectacular and beautiful bird

to Princess Sirindhorn Thepratanasuda. Over the

next three years several more specimens were collected

at the same site, but apart from these, and a

fleeting observation in 1978, this remarkable

bird has effectively vanished. An avian enigma,

it has come to epitomise the mythical allure of

rarity to the birdwatcher, and for three decades

it has symbolised the Asian mystery of the ornithological

world. As such it has appeared in logo form in

the pages of this journal as the archetypal little-known

bird. The time has come to compile our knowledge

of the species and to present it afresh in the

hope that it might lead to a dramatic rediscovery.

Paragraph 2 To begin

with, we need to retrace the events of January

and February 1968 and glean what we can from the

available facts. The site of discovery is first

misleadingly given as a big marsh on the Chao

Praya River (1). The type-locality is then specified

as Bung (= Nong = Lake) Boraphet, Amphoe Muang,

Nakhon Sawan Province, central Thailand (1), and

from its subsequent description as a shallow,

marshy, reed-filled lake of 25,000 hectares it

seems clear that this is the big marsh originally

mentioned (a point confirmed by Thonglongya (2)).

Rediscovery efforts in 1980-1981 were apparently

concentrated on an island where all of Kitti's

river martins had been captured (3), suggesting

that, at one time, confidence was high that a

very precise origin was known.

Paragraph 3 This

no longer appears to be the case. The first White-eyed

River-Martins were reportedly caught while night-trapping

roosting swallows (Hirundo rustica, H. daurica,

Riparia riparia), wagtails and warblers by

casting a fishing net over a reedbed (1) a method

repeated by subsequent authors (3,4,5). However,

according to a local technician who worked with

the original field team, the birds were neither

seen in the field nor trapped by any of the team

members, but rather were brought in to the teams

hotel in nearby Nakhon Sawan by villagers following

a broadcast appeal for live wild birds for ringing

purposes (6). It seems likely, therefore, that

the precise site of collection is impossible to

determine, but that it is certainly in the region

of Bung Boraphet, and most likely at the lake

itself.

Paragraph 4 Whatever

their exact origins, nine specimens were initially

collected: one each on 28 and 29 January (although

the label on specimen 53-1218 actually states

27 January 1968 (6)) and seven on 10 February

1968 (1). From analysis of the resultant skins

its closest ally was deemed to be the African

River-Martin Pseudochelidon eurystomina

(1). Initially described as congeneric (1), the

African species and the Asian species differ markedly

in the size of their bills and eyes, suggesting

that they have very different feeding ecologies,

sirintarae probably being able to take

much larger prey and perhaps in different microhabitats

(7). The gape of sirintarae is swollen and hardened,

unlike the softer, fleshier, much less prominent

gape of eurystomina(1,19). The feet and claws

of sirintarae are unusually large and

robust for an aerial feeder (1) and the two species

also have different toe proportions, which might

suggest dissimilar nesting habits (19). These

differences are sufficiently pronounced in the

view of some taxonomists to permit the allocation

of its own genus, Eurochelidon (7), although

other authors support the retention of both species

in Pseudochelidon, arguing that they

mirror patterns in other congeneric hirundines

(8). Whether treated as one genus, or two, the

syringeal structures of the two river-martins

are divergent enough from those of the Hirundininae

to confirm subfamily distinction from the true

swallows, and apparently enough to suggest that

they might belong in a separate family (1,9).

Paragraph 5 Shortly

after these first specimens, a tenth bird was

caught in November 1968 (2) and brought alive

to Bangkok where it was photographed in December

1968 (3). Furthermore, at least two birds (one

pair) reached but soon afterwards died in Dusit

Zoo in Bangkok in early 1971 (3). The only widely

reported field observation was of six individuals

flying low over Bung Boraphet towards dusk on

3 February 1978 (10). In addition, four probable

immature White-eyed River-Martins were reportedly

observed perched in trees on Temple Island in

Bung Boraphet in January 1980 (3,5), and one was

reputedly trapped by local people in 1986 (11).

Both these records remain unconfirmed. Several

subsequent searches have tried to locate the species

around the site. For example, eleven amateur birding

groups surveyed the lake unsuccessfully during

1979 (3). Investigations were carried out between

December 1980 to March 1981 by a team from the

Association for the Conservation of Wildlife but,

despite netting many roosting Barn Swallows in

reedbeds, they failed to reveal any river-martins

(12). In 1988 another concerted effort to relocate

the species was undertaken at Bung Boraphet, ending

with failure as the swallow roosts were highly

disturbed and mobile (13).

Paragraph 6 The

real number of White-eyed River-Martins trapped

in the 1960s and 1970s may have been much higher

than these figures suggest. In the wave of public

and media interest following the sensational discovery

of the species, trappers are rumoured to have

caught around 120 individuals and sold them to

the director of the Nakhon Sawan Fisheries Station

(3,5). Moreover, local markets were reported to

have had several other specimens in January-February

of succeeding years (10). Having been found on

Thai soil and decorated with the name of Thai

royalty, there was a significant local demand

for specimens or caged examples of the species,

for zoos, presentation to dignitaries or as curios

for the affluent.

Paragraph 7 What

has become of the White-eyed River-Martin? Did

this harvest of hirundines extinguish it entirely?

Were these last known individuals merely the doomed

remnants of a population displaced by disturbance

from a specialised breeding habitat? (5) Perhaps.

It is quite conceivably extinct, and if it still

survives its population seems likely to be tiny.

The original series of specimens taken in early

1968 were outnumbered by hordes of trapped Barn

Swallows by a ratio of 9:6,000 (1). In spite of

this exceptional rarity, it was thought that the

species might be regular at Bung Boraphet since

the local bird-catchers had a name for it, nok

ta phong, the swollen-eyed bird (1). Unfortunately,

there has been a drastic decline in the Bung Boraphet

swallow population from hundreds of thousands

reported around 1970 to maximum counts of 8,000

made in the winter of 1980-1981, although it is

not certain if this represents a real decline

or a shift in site in response to persecution

(3). However, an estimated 100,000 swallows were

present at a roost near Chotiravi, near Bung Boraphet,

in August 1986 (11) and there were 30,000 at Bung

Boraphet in May 1988 (11). Nevertheless, a dealer

working the large Chotiravi roost claimed never

to have encountered the species (11). The general

feeling is that an absence of sightings since

early 1980, despite numerous observational efforts,

cast ominous doubts over the survival of the White-eyed

River-Martin (3).

Paragraph 8 Unfortunately,

the habits of swallows around the lake appear

to have altered recently, with very few birds

roosting in the reedbeds until late winter (13).

Much of the population now roosts in sugar cane

plantations, moving back to the reedbeds after

the cane has been harvested (13). The roosts also

form well after dark, whereas they once gathered

before dusk (13). These changes are probably the

result of prolonged disturbance by trappers (11).

In any case, the swallow roosts are more mobile

and difficult to locate, factors that have further

obstructed the rediscovery of the White-eyed River-Martin.

Paragraph 9 The

reduction in Barn Swallow populations in the Bung

Boraphet area is difficult to explain but intensive

trapping activities for the purpose of selling

birds as food in local markets must have played

a major role, as must the annual destruction of

roosting sites to make way for lotus cultivation

(3). Huge areas of reedbed in areas frequented

by roosting swallows were being burnt in February

1986 (11). The hunting of hirundines without a

licence has been illegal since 1972, although

this legislation is rarely enforced (3). Relations

between conservationists and bird trappers at

Bung Boraphet are occasionally fraught, to the

extent that a reserve ranger was killed when trying

to apprehend poachers at roosts in 1987 (13).

Paragraph 10 It

seems that any rediscovery efforts should now

be targeted away from Bung Boraphet, and indeed

perhaps away from Thailand. How might we judge

where best to look? What secrets have hitherto

been disclosed that might help direct our search?

Unhelpfully, the ecology of this bird remains

almost totally unknown, and thus ornithologists

have looked to its presumed relative, the African

River-Martin, to provide clues. Since P. eurystomina

feeds largely over both forest and open grassy

country, nesting colonially in tunnels dug in

sandbars of large rivers (14) it has been inferred

that E. sirintarae possibly does or once did the

same (4). However, the differently shaped toes

might suggest otherwise (19). At least one of

the initial specimens had mud or sand adhering

to its claws, and while this perhaps suggests

a terrestrial perching habit (6), most swallows

occasionally do the same, especially when collecting

nest material. Another clue: in holding cages

used during the swallow ringing programme, the

birds stood quietly in the corner of the cage

in strong contrast to other swallows which move

rapidly from perch to perch calling repeatedly

(1).

Paragraph 11 In

the unconfirmed report of 1980, individuals were

flying after insects with some Barn Swallows and

sometimes perching on the tops of trees (20).

During the 1978 sighting they were apparently

skimming the water surface, possibly to drink

(10). While these accounts describe behaviour

characteristic of most swallows, the only direct

dietary evidence is the fragment of a large beetle

found in the stomach of a specimen (1). This fact,

along with the mandibular morphology of the species,

implies that it consumes sizeable prey.

Paragraph 12 What

about breeding season, distribution and migratory

behaviour? Five of the nine specimens collected

in late January and early February 1968 were immature

(1); they were later termed juvenile, and some

of the other material as subadult (2) (although

this is not mentioned in the original description).

A breeding site within Thailand was initially

considered plausible on the grounds that so many

of the type series were young (2). It has also

been speculated that if nesting occurs in Thailand

it is most likely to do so between March and April,

as this coincides with the local nesting season

for the majority of insectivorous birds, while

the monsoon rains from May onwards presumably

raise water levels above the riverine sandflats

postulated to be the favoured nesting habitat

of the species (5,6,10). It is unlikely, however,

that juvenile plumage would be retained for eight

months, and thus these two facts are difficult

to reconcile. The White-eyed River-Martin has

otherwise been thought a non-breeding visitor

to south-central Thailand (20) and clearly migratory

(4), but these assumptions should also be treated

with care. Although it has only been found between

December and February, and despite the above disparity,

there is insufficient information to rule out

breeding in the Nakhon Sawan area (6,11). In conclusion,

it is unclear whether the species is, or was,

a migrant at all.

Paragraph 13 As

recent searches around Bung Boraphet have been

unsuccessful, let us assume it is a migrant. If

it travelled across Thailand, where did it come

from? The riverine nesting grounds might possibly

lie along one of the four major watercourses (the

Ping, Wang, Yom and Nan) which drain northern

Thailand, either in the immediate vicinity of

Nakhon Sawan or to the north (5,6). If it came

from further afield, perhaps these putative breeding

grounds lie on one of the other major river systems

of South-East Asia, such as the Mekong in China,

Laos or Cambodia, or the Salween and Irrawaddy

in Myanmar (5,6). Evidence that the species breeds,

or has ever occurred, in China is scant, although

a painting by a Chinese artist held in the Sun

Fung Art House of Hong Kong appears to depict

the species (15). This tentative clue has failed

to lead to any further information, and in any

case the subject of the painting is more likely

to be an Oriental Pratincole Glareola maldivarum

(16).

Paragraph 14 A survey

of the Nan, Yom and Wang rivers in northern Thailand

was carried out in May 1969, but was not comprehensive

and relied chiefly on interviewing villagers,

none of whom seemed to know the bird (2). Rivers

near the Chinese border of Laos were searched

in April 1996, local people being shown illustrations

of the species, but without success (W. Robichaud

verbally 1997). Very few other surveys have looked

for it outside Thailand and there is still scope

for research in remote regions where a population

might survive.

Paragraph 15 Throughout

its possible range there is a catalogue of pressures

potentially imposed on the species (5,6). Man

has drastically altered the lowlands of central

and northern Thailand: huge areas are now deforested,

agriculture has intensified, pesticide use is

ubiquitous and urban environments have spread

extensively (5,6). In addition, all major lowland

rivers and their banks suffer a high level of

disturbance by fishermen, hunters, vegetable growers

and sand-dredgers (5,6). Whole communities of

nesting riverine birds have vanished from large

segments of their ranges in South-East Asia owing

to habitat destruction, human persecution and

intense disturbance of most navigable waterways

(5,17,18). Local people routinely trap or shoot

birds for food and for sale in local markets (5,6).

Even at Bung Boraphet Non-Hunting Area (established

in 19793) the trapping of birds has continued,

at some level, up to the present (5,6). If the

species preferentially forages over forest, its

numbers could already have declined to a perilously

low level at the time of its discovery because

of deforestation and the intensification of agriculture

in river valleys (5,6).

Paragraph 16 These

threats are based on the ecological traits inferred

by its suspected taxonomic affinities. It should

be borne in mind that riverine nesting habits

and preferences for forest are only an assumption,

and that it might conceivably utilise some entirely

different habitat. Even the name river-martin

is perhaps a complete misnomer, as the species

has never been seen on a river and is no longer

considered congeneric with the African River-Martin

(7). Interestingly, the most recent scrutiny of

specimens suggested that it was perhaps nocturnal,

or at least highly crepuscular, based principally

on its unusually large eyes (19). This raises

the possibility that it is normally a cave dweller

or a hole-rooster in trees or rock, emerging to

feed in twilight or darkness, and this opens up

new avenues of exploration. There are, for example,

limestone caves not far from Bung Boraphet, and

many more in Laos and southern China.

Paragraph 17 While

there is only a faint chance that this, one of

the most elusive species in the world (15) still

survives, it bears the extraordinary distinction

of being highly unusual in appearance yet overlooked

by naturalists in a well-worked country until

the late 1960s. As it is thus either extremely

rare or inexplicably cryptic, it is not yet time

to give up hope for the swollen-eyed bird. Its

possible range should be revisited with a broader

outlook. The prize, to any successful searcher,

is considerable: solving one of the most puzzling

mysteries of Asian ornithology.

References

1. Thonglongya, Kitti (1968) A

new martin of the genus Pseudochelidon

from Thailand. Thai

National Scientific Papers, Fauna Series no. 1.

Bangkok: Applied Scientific Research

Corporation of Thailand.

2. Thonglongya, Kitti (1969) Report

on an expedition in northern Thailand to look

for breeding

sites of Pseudochelidon sirintarae (21 May to

27 June). Bangkok: Applied Scientific Research

Corporation of Thailand

3. Sophason and Dobias (1984)

The fate of the Princess Bird, or White-eyed River

Martin

(Pseudochelidon sirintarae). Nat.

Hist. Bull. Siam Soc. 32(1):

1-10.

4. Turner and Rose (1989) Swallows

and martins of the world. Bromley, UK: Christopher

Helm.

5. Round, P. D. (1990) Bird of

the month: White-eyed River-Martin. Bangkok

Bird Club Bulletin 7(1):

10-11.

6. BirdLife International (in

press) Threatened birds of Asia.

7. Brooke, R. K. (1972) Generic

limits in old world Apodidae and Hirundinidae.

Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 93:

53-57.

8. Zusi, R. L. (1978) Remarks

on the generic allocation of Pseudochelidon

sirintarae. Bull. Brit.

Orn. Cl. 98(1): 13-15.

9. Mayr, E. and Amadon, D. (1951)

A classification of recent birds. Amer.

Mus. Novit. 1496: 1-42.

10. King and Kanwanich (1978)

First wild sighting of the White-eyed River-Martin,

Pseudochelidon sirintarae. Biol.

Cons. 13: 183-185.

11. D. Ogle in litt.

(1986).

12. Anon. (1981) A search for

the White-eyed River Martin, Pseudochelidon

sirintarae, at Bung

Boraphet, central Thailand. Bangkok: Association

for the conservation of Wildlife of Thailand.

Unpublished report.

13. D. Ogle in litt.

(19871988).

14. Keith. S., Urban, E. K. and

Fry, C. H. (1992) The Birds of Africa,

volume 4. London: Academic

Press.

15. Dickinson, E. (1986) Does

the White-eyed River-Martin Pseudochelidon

sirintarae breed in

China? Forktail 2: 95-96.

16. Parkes, K. C. (1987) Letter:

was the Chinese White-eyed River-Martin an Oriental

Pratincole?

Forktail 3: 68-69.

17. Scott, D. A. (ed.) (1989)

A Directory of Asian Wetlands. IUCN,

Gland, Switzerland and

Cambridge, UK.

18. Duckworth, J. W., Salter,

R. E. and Khounboline, K. (compilers) (1999) Wildlife

in Lao PDR:

1999 Status Report. Vientiane: IUCN-The World

Conservation Union/Wildlife Conservation

Society/Centre for Protected Areas and Watershed

Management.

19. P. M. Rasmussen in litt.

(2000).

20.

Ogle, D. (1986) The status and seasonality of

birds in Nakhon Sawan Province, Thailand. Nat.

Hist. Bull. Siam Soc. 34:

115-143. |

|

|

| |

|

| Site

map : Contributors |

|

Copyright © 2004-2006 thaibirding.com. All

rights reserved. |