|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Favorite Tweets by @thaibirding | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Buy Birds of Thailand on Amazon.co.uk |

||||||||||

| Site Map ; Contributors |

| Shorebirds

in the Inner Gulf of Thailand By Philip D. Round |

| Tweet |

Note: This article was originally published in Stilt 50 (2006) the journal for the Australasian Wader Studies Group and was kindly submitted by Philip D. Round. Please support the AWSG's conservation work by visiting the AWSG website and becoming a member. |

| INTRODUCTION As a predominantly lowland country with a long shoreline, Thailand is of major importance for waterbirds, both passage and wintering species, and residents and local dispersants. A total of 64 species of shorebirds are found both in coastal mudflat and mangrove habitats, and also inland on the paddylands and marshes of alluvial basins; many of these species occur in internationally important concentrations. Scott (1989) listed 42 sites in Thailand that were wetlands of probable international importance, while Tunhikorn & Round (1995) considered that 14 sites, nine coastal and five inland, were of international importance for waders. In view of the time that has elapsed since the latter review, and the great amount of new information collected, an up-date on Thai wader sites would be timely. I focus here on one of these, the Inner Gulf, probably Thailand’s single most important wetland site because of the numbers and species diversity of shorebirds it supports. Southern Hemisphere readers should note that the winter referred to here is the Northern Hemisphere winter, the nonbreeding season for Arctic breeders. |

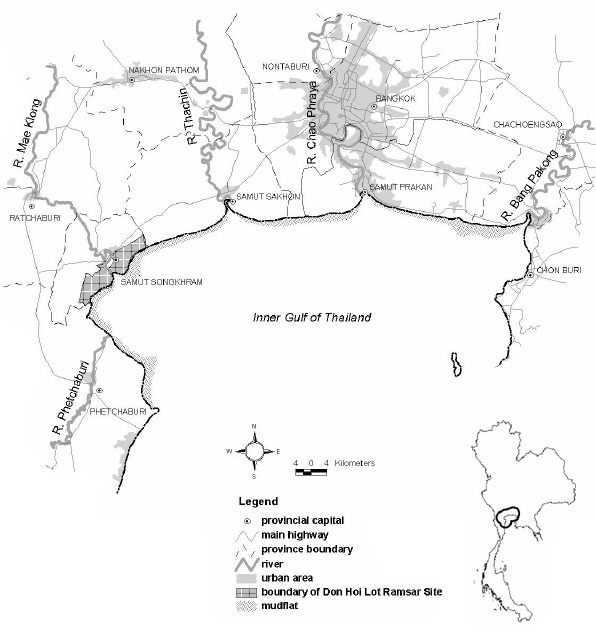

| THE

STUDY AREA Extending east and west of the city of Bangkok, the Inner Gulf encompasses a roughly 100 km length of shoreline at the head of a 350,000 km2 enclosed shallow bay (45–80 m depth), lying on the Sunda Shelf. In addition to the delta of the Chao Phraya River (on which Bangkok is situated), the Inner Gulf also encompasses the mouths of the Bang Pakong River to the east, and three further rivers to the west, the Thachin (a deltaic branch of the Chao Phraya), the Mae Klong (better known as the River Kwai), and the much smaller and shorter Phetchaburi River (Figure 1). Together these areas form the second or third largest river delta in south-east Asia. |

Figure 1: Inner Gulf of Thailand |

| Roughly

800–1000 km2 of mudflats, salt-pans, prawn-capture ponds and

unused coastal flats lie adjacent to, and grade into, one of the largest

rice-growing areas in the world, Thailand’s Central Plains.

There is a long history of human use of coastal habitats in the Inner

Gulf. Salt-pan usage in the western parts of the area dates back perhaps

800 years (Reid 1988) and salt pans continue to occupy c. 106 km2.

Low intensity prawn-capture ponds including some abandoned, unutilised

areas occupy around 400 km2 while approximately 235 km2 of mudflats

lie offshore (Erftemeijer & Jukmongkol 1999). Mangroves (129 km2)

are now limited to a narrow (100–200 m wide) belt along the

coast, with largest areas (approximately 80% of the total) in the

western gulf, around Phetchaburi. Clearance of mangroves probably

took place as long as 100 years ago, and the area remaining is largely

secondary regrowth, dominated by Avicennia spp., Rhizophora

mucronata and R. apiculata. The tidal pattern is characterised as mixed semi-diurnal; two high and two low tides occur each lunar day, but one tide is much smaller and often negligible. During much of December and January, for example, the tidal flats of the Inner Gulf are inundated throughout the daylight hours and exposed only during the hours of darkness. Thus mudflat usage cannot be assessed at that season. Human use of the Inner Gulf is intensive. In addition to onshore activities, the mudflats are exploited for molluscs, and coastal waters support inshore fisheries for fishes, molluscs and crustacea, and plankton. |

| HISTORY

OF WADER STUDIES The importance of the site for waterbirds, and especially as a wintering and staging area for migratory shorebirds, has long been recognized. W.J.F. Williamson collected Great Knots, Asian Dowitchers and a range of other shorebirds from the gulf early in the twentieth century (Williamson 1918), as did C.J. Aagaard a decade or so later (Jørgensen 1949). Only a handful of shorebirds numbered among the more than 185,000 birds banded in Thailand during the (1963–1971) Migratory Animals Pathological Survey (McClure 1974). Small-scale banding and surveys of shorebirds have taken place from 1980 onwards (e.g. Melville 1982, Parish & Wells 1985), and more recently, since September 2000, by the author and colleagues. Since September 2005, all shorebirds banded in the Inner Gulf have been marked with leg-flags under the East Asian–Australasian Shorebird Flagging Protocol. Observer coverage of the gulf has improved markedly since 1999. In particular, better access to, and knowledge of, shorebird habitats in the western sectors of the gulf has greatly improved our understanding of the status of many species, and led to the discovery of a regular wintering population of Nordmann’s Greenshanks and two regular wintering locations for Spoon-billed Sandpipers. Extensive midwinter coverage of the Inner Gulf during the Asian Midwinter Waterbird Census (AWC) was achieved in three years since 2000 (2000, 2005 and 2006). Many birdwatchers and photographers who are now active around Bangkok have contributed greatly to recent coverage. |

| STATUS

OF SHOREBIRDS Fifty-six shorebird species have occurred in the Inner Gulf (Table 1); 49 species are winter visitors or passage migrants. Seven species breed locally: Pheasant-tailed Jacana, Bronze-winged Jacana, Black-winged Stilt, Eurasian Thick-knee, Oriental Pratincole, Red-wattled Lapwing and Malaysian Plover. |

| Table

1: Shorebirds known from the Inner Gulf of Thailand. Largest

midwinter counts are the largest single site concentration or largest

coordinated count made within the study area. Maximum counts are provided

where these are larger than midwinter numbers. Waterfowl populations

exceeding 1% of the estimated flyway population levels (following

Wetlands International, 2002) are considered globally significant

according to criteria set down by the Ramsar Convention. Numbers and

concentration in Inner Gulf of probable international importance or

definite international importance according to currently accepted

criteria. Asterisk (*) indicates figure for 1% level no longer applicable

due to recent findings; that for Oriental Pratincole is now much larger

than listed (Sitters et al., 2004) while that for Spoon-billed

Sandpiper is now thought to be much lower (Zöckler et al.,

2006). In the count columns: na = Not available. Source: Round and

Gardner in press; unpubl. AWC results from January 2006.

|

| Numbers

presented are midwinter count maxima. Midwinter concentrations of

20 species are thought to be of international importance. The most

numerous wintering shorebirds are Lesser Sand Plover (6,298), Red-necked

Stint (3,447), Black-tailed Godwit (3,078), Marsh Sandpiper (2,324),

Black-winged Stilt (2,726), and Common Redshank (1,523). Based on

allowance for turnover, Erftemeijer and Jukmongkol (1999) estimated

the numbers of wintering and staging shorebirds that use the site

as 100,000–135,000 per year, and the numbers using the site

in midwinter as 30,000– 40,000. Indications are that the western sectors of the gulf receive higher usage than the sectors to the more heavily industrialised east of the Chao Phraya River, where it is thought that mudflat usage may be constrained by a shortage of suitable onshore roosting areas (see below under Status of Habitats). Globally threatened species Small numbers of Spoon-billed Sandpipers are now known to winter at two localities in the Inner Gulf, having first been recorded in 1995, and have been found in every winter period since late 1999. The largest single site count is 16 birds. Most sightings have been made on temporarily out-ofuse, shallow-flooded salt pans where the birds evidently feed. The first birds arrive in mid-October and remain until mid-April (exceptionally early May). A regular presence of Nordmann’s Greenshank at two localities in the Inner Gulf has only been recognised since November 2003. The largest single count was a single flock of 60 birds on 24 December 2005 while up to 30 birds have been seen at a second site some 60 km distant, so there could potentially be as many as 90 birds wintering in total. There is very little local information on ecology since most birds have been roosting on ponds at high tide during the daylight hours and are presumed to fly out to feed on mudflats as the tide drops, usually during the hours of darkness. Breeding populations Undoubtedly the most important shorebird breeding population is that of Black-winged Stilt. Nesting of this species on coastal flats near Samut Sakhon was mentioned by Madoc (1950), and breeders are common and widespread, laying their eggs on, for example, pond margins in brackish water areas in the coastal zone but also on floating vegetation in freshwater sites well inland. There have been no counts of the breeding population, though it probably numbers over 1000 pairs. Those recorded in winter (~3000) are assumed to be mainly or entirely local birds, although the occurrence of northern migrants is also to be expected. Roughly 10–15 pairs of Malaysian Plovers nest at the south-west margins of the gulf, on the site’s only sand-beach habitat, on an accreting 3 km long sandspit. Although this is not the largest single population, it is of national significance, given the threats from disturbance posed by tourism at other, more extensive sand-beach habitats elsewhere in the peninsula. The Inner Gulf as a staging area for migrants Counts are too few, and coverage too uneven, to be able to reliably chart seasonal changes in numbers in the many shorebirds in the gulf. Paradoxically, midwinter counts for most species now generally outnumber those during spring and autumn, perhaps because those seasons are less wellsampled, and also due to turnover. The clearest evidence of the importance of the Inner Gulf as a staging area comes from observations of Asian Dowitcher. The c. 400 Asian Dowitchers observed in the Inner Gulf in April 1984 (Round 1985) was then the largest number known anywhere until a major wintering concentration in Sumatra was discovered in the autumn of that same year. Although Asian Dowitchers are now known to winter in the gulf in significant numbers (Table 1), midwinter numbers are greatly exceeded by spring maxima, usually recorded in the first half of April. In autumn, Asian Dowitchers begin to arrive in mid- to late July and passage continues into October, though numbers are generally lower than those in spring, perhaps because the passage is more protracted. Small numbers of Grey-tailed Tattlers are also recorded on spring and autumn passage; none winter. Most other species are recorded both on passage and in midwinter. Flag-sightings and recoveries/controls have also begun to inform on movements. Two flag-sightings and one control indicate that some Common Redshanks that move through the Inner Gulf migrate further, to winter in West Malaysia or Singapore. Sightings of a Singaporean leg-flagged Lesser Sand Plover, and of Curlew Sandpipers from north-west and southern Australia, and Red-necked Stints from the east Asian seaboard have also been reported (Table 2). All Lesser Sand Plovers handled, and those observed in breeding dress in spring, have shown the characteristics of the atrifrons group of races that breed in central Asia. So far as known there are no records in Thailand of the north-east Asian breeding mongolus, which presumably passes further east. |

Table

2: Trans-national recoveries or resightings of shorebirds

from the Inner Gulf of Thailand |

| Changes

in status of species Trends in numbers through time cannot be tracked reliably for most species. Although recorded maxima for most have increased in recent years, this is almost certainly due to better coverage. An increase in the wintering population of Black-tailed Godwits Limosa limosa appears, however, to be genuine as the numbers at a single frequently covered site (Bang Pu) increased from 300 in December 1996 to 800 in December 1997, and 1,200 one year later (Round & Gardner, in press). The midwinter count throughout the gulf in January 2006 was 3,078. Increased numbers of Great Knots (previously thought to be only a spring and autumn passage migrant) have also been recorded in midwinter. Roughly 60 were counted in year 2000, but 800 in January 2005, and over 1,450 in January 2006. The trend detected in Asian Dowitcher runs counter to that for most other shorebirds and is possibly of concern. Single day concentrations of 200–400 birds were regularly found in spring during the 1980s. The largest reliably documented count is 600 birds on 22 April 1989 (Round & Gardner, in press) although there are anecdotal reports of “about one thousand” during peak spring passage. Coverage during April has subsequently been very limited, and relatively few have been recorded in recent years (maximum 93 in April 1999; Erftemeijer and Jukmongkol 1999) and during March–May 2006 (120; S. Nimnuan, in litt.) indicating that further study is needed. It is not clear whether this represents a genuine decline in the population using the gulf, or a local shift in areas used so that some birds remained undetected. |

| OTHER

WATERFOWL Other than shorebirds, there are at least another 11 species of waterbird for which the populations in the Inner Gulf are of known, or probable, international importance (Round & Gardner, in press). These are: Brown-headed Gull Larus brunnicephalus, Caspian Tern Sterna caspia, Common Tern S. hirundo, Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybrida, Little Cormorant Phalacrocorax niger, Indian Cormorant P. fuscicollis, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Great Egret Casmerodius albus, Javan Pond Heron Ardeola speciosa, Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis and Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala. The number of Brown-headed Gulls, roughly 10,000 of which winter, may be one of the largest wintering concentrations known. |

| STATUS

OF HABITATS The importance of the Inner Gulf is owed largely to the relatively great expanse of low intensity ponds, so-called “supratidal habitats” that occur in proximity to the extensive mudflats. While the importance of traditional aquaculture ponds and salt-pans as shorebird roosting areas has long been recognised, such areas also provide feeding habitat, with shorebirds showing similar rates of energy intake on salt pans as they do on semi-natural wetlands (Yasué and Dearden, in prep.). For some species, such as Long-toed and Red-necked Stints, and Broad-billed Sandpipers, salt-pans possibly support the majority of birds throughout all stages of the tidal cycle. Industrial and urban expansion The integrity of the Inner Gulf is threatened by a number of factors. Virtually none of this onshore habitat is protected; no zoning is in place to prevent piecemeal loss from landspeculation, creeping urbanisation, and industrialisation associated with the spread of Bangkok and the provincial capitals of Samut Prakan, Samut Sakhon, Samut Songkhram and Phetchaburi. The area has suffered from a proliferation of inappropriate constructions, and ribbon development along some roads. In addition, several new highways are either being constructed, or are planned within the coastal zone. The eastern sectors of the gulf, to the east of the Chao Phraya River, have borne the brunt of the industrialisation up to the present. However, industrialisation of the western sectors is now beginning, with the construction of an oilrefinery on 1 km2 of land close to one of the two Spoon-billed Sandpiper wintering areas on the Inner Gulf (Manopawitr and Round 2004). Loss of mudflats Although mudflat reclamations have occasionally been proposed, no reclamation on any significant scale has taken place. A more significant threat is posed by coastal erosion. Over 80% of the shoreline is suffering erosion rates of 5–25 m/year (study on coastal change by the Department of Mineral Resources; data supplied by N. Chaimanee, in litt.). The problem is compounded by the extraction of groundwater for industrial and household use, which causes compaction of sediments and land subsidence, and also by reduced outflow of sediments from the major rivers, most of which are dammed. Responses to erosion include ad hoc mangrove plantings on mudflats (which may exacerbate the loss of shorebird feeding areas), and the construction of concrete sea-walls or boulder embankments on some stretches of shoreline, which may alter tidal flow pattens and worsen erosion on unprotected sections of coast. Changing land-use The Inner Gulf was spared the worst of the (post-1980) boom in intensive prawn-farming which has blighted many areas of south-east Asia and which would have destroyed or damaged onshore feeding and roosting areas for shorebirds. Following an initial boom in the mid- to late 1980s, poor water circulation and inappropriate management caused the industry to collapse within about four years (around 1990) due to the proliferation of fungal diseases and the accumulation of pollutants. Most areas then reverted to low intensity prawn-capture ponds including some abandoned, unutilised areas, which continued to support significant numbers of shorebirds. The cycle may now, however, be being repeated. The current practice in some areas is to remove the accumulated pond sediments for landfills, converting once shallow, traditional ponds into deep, steep-sided ponds for aquaculture of prawns and crabs combined, or in some cases for cultivation of molluscs. If the trend towards conversion to deep water-filled ponds continues, this will greatly reduce onshore feeding and roosting areas for waders, and could conceivably increase the susceptibility of the coastal zone to erosion, or perhaps even catastrophic tidal breach. Another disturbing trend is the use of polythene pondliners on salt pans in some areas, rendering them unavailable as feeding areas. So far, however, use of these is limited. Pollution A wide array of organic and inorganic pollutants enters the gulf and, because of poor circulation, they tend to accumulate. However, there are no data on the effects of these on waterbirds. Occasional deaths of small numbers of birds have been recorded, possibly associated with dinoflagellate blooms. Hunting Direct persecution of shorebirds (netting for supply to local markets as food) still occurs, but probably on too small a scale to have a major impact. Awareness is generally high and most species are fully protected in law under the Wild Animal Reservations and Protection Act (1992). |

CONSERVATION

STATUS Approximately 24 km2 of coastal habitats, and an undetermined area of offshore mudflats and shallow coastal waters at Don Hoi Lot in the western sector of the gulf, were declared as a Wetland of International Importance under the Convention on Wetlands. However, the area receives no special protection in law and, additionally, offshore flats receive heavy human use from shellfish collectors so that shorebird usage is relatively low compared with some other sectors that receive no special recognition. Although the government has prepared its own national inventory of wetlands (OEPP 1999; 2002), the Inner Gulf, listed as of international importance by IUCN (Scott 1989), was perversely downgraded to only national importance in the national inventory. This suggests that designation was not based on objective scientific criteria, and that the lowered importance level of the Inner Gulf may have been due to political pressure applied to the inventory compilers. To summarise, the Inner Gulf of Thailand is one of the most important coastal wetlands in Asia, yet also one of the most threatened. It is accorded no special recognition by government agencies, even though Thailand is a party to the Convention on Wetlands. |

| RECOMMENDATIONS

FOR FUTURE WORK 1) Monitoring of numbers and usage. There is a clear need for more frequent and systematic counting of shorebirds throughout the Inner Gulf so as to better track numbers and usage. In particular, more emphasis needs to be placed on: i) identifying key mudflat feeding areas; ii) investigating how differential usage of feeding areas relates to the density and distribution of shorebird prey; and iii) investigating how conditions of onshore habitats influences mudflat usage. 2) Determining origins and movements of birds through increased emphasis on banding and colour-flagging. 3) Increasing awareness of the importance of the Inner Gulf among Thai government agencies. Sufficient information already exists to warrant nomination of at least the western sectors of the Inner Gulf as a shorebird reserve network site, and such a designation would usefully provide focus for those government agencies involved in coastal resource management. Additional information on shorebirds that is collected could be integrated into a comprehensive zoning plan for coastal habitats in the gulf. |

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand and the many shorebird watchers who have contributed to our knowledge of waders in the gulf, and Wetlands International and The Wetland Trust (UK) for providing support. Sittichai Jinamoy (Hornbill Project Thailand) prepared the figure. |

| REFERENCES Erftemeijer P.L.A. & R. Jukmongkol. (1999). Migratory Shorebirds and their habitats in the Inner Gulf of Thailand. Wetlands International Publication No. 13. Wetlands International and Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, Bangkok and Hat Yai, Thailand. Jørgensen, A. (1949). Siams vadefugle. Dansk. Orn. Foren. Tidsskr. 43: 60–80; 150–162; 216–237; 261–279. McClure, H.E. (1974). Migration and Survival of the Birds of Asia. Applied Scientific Research Corporation of Thailand, Bangkok. Madoc, G.C. (1950). Field notes on some Siamese birds. Bull. Raffles Museum 23: 129–190. Manopawitr, P. & P.D. Round. (2004). Site to watch: Thailand’s greatest wetland under imminent threat. BirdingASIA 2: 74–77. Melville, D.S. (1982). Shorebird studies in the Inner Gulf of Siam by the Association for the Conservation of Wildlife. Winter 1980/81. Unpubl. report. Office of Environmental Policy and Planning. (1999). Wetlands in the Central and Eastern Regions. Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment. Bangkok. (In Thai.) Office of Environmental Policy and Planning. (2002). An inventory of wetlands of international and national importance in Thailand. Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment. Bangkok. Parish, D. & D.R. Wells. (eds) (1985). Interwader Annual Report 1984. Interwader, Kuala Lumpur. Reid, A. (1988). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450– 1680. Vol. 1: The Lands below the Winds. Yale University Press, New Haven. Round, P.D. (1985). Records of the Asian Dowitcher Limnodromus semipalmatus in Thailand. Oriental Bird Club Bulletin 1: 5–7. Round, P.D. & D. Gardner. (in press). The Birds of the Bangkok Area. White Lotus, Bangkok. Scott, D.A. (ed.). (1989). A Directory of Asian Wetlands. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. Sitters, H.P., C. Minton, P. Collins, B. Etheridge, C. Hassell & F. O’Connor. (2004). Extraordinary numbers of Oriental Pratincoles in NW Australia. Stilt 45: 43–49. Tunhikorn, S. & P.D. Round. (1995). The status and conservation needs of migratory shorebirds in Thailand. Pp. 119–132 in D.R. Wells and T. Mundkur, Conservation of Migratory Waterbirds and their Wetland Habitats in the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. Proceedings of an International Workshop held at Kushiro, Japan, 28 November–3 December 1994. Publication No 116, Wetlands International, Asia Pacific, Kuala Lumpur. Wetlands International. (2002). Waterbird population estimates. 3rd edn. Wetlands International Global Series No. 12. Wageningen, The Netherlands. Williamson, W.J.F. (1918). New or noteworthy bird-records from Siam. Journ. Nat. Hist. Soc. Siam 3 (1): 15–42. Yasué, M. & P. Dearden. (in prep.) The importance of supratidal habitats for wintering shorebirds and the potential impacts of intensive shrimp aquaculture. Zöckler, C., E.E. Syroechkovski Jr, E.G. Lappo, & G. Bunting. (2006). Stable isotope analysis and threats in the wintering areas of the declining Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus in the East Asia-Pacific Flyway. Proceedings of the Waterbirds Around the World Conference. |

| Kindly

submitted by: Philip D. Round, Assistant Professor and Regional Representative, The Wetland Trust, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Rama 6 Road, Bangkok 10400, Thailand Email: frpdr@mahidol.ac.th |

| Tweet |

A Guide to Birdwatching in Thailand. Copyright © 2004-2017 thaibirding.com. All rights reserved.